There are three primary benefits to the students, Adam said.

First, they learn that they have the right to question things, and more importantly, to try and change what they believe is not right. Presently, Critical Exposure fellowship students are using their photography and advocacy skills to protest the school-to-prison pipeline, which pushes at-risk students, often minorities, out of the education system and into the penal one.

Second, they learn the power of collaboration and working together.

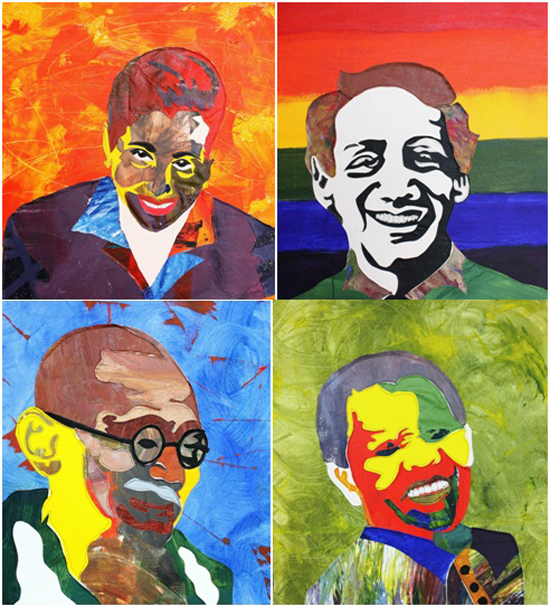

And third, they get to see that people value what they have to say. “The young people we work with are often told they don’t have anything to say of value,” said Adam, “so for them to testify in front of city council, or to have their photos at an art gallery, is validating for them.”

Worth a Million Words

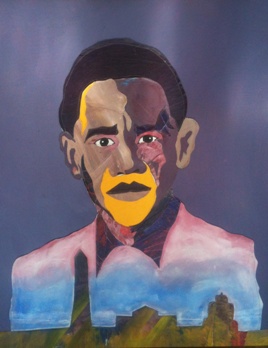

As a teenager, Delonte Williams wasn't headed down what one might call the right path. He had, he said, an "I don't care" attitude.

"I was willing to put myself in a bad situation," he said. "I was exposed to hurt and I never found anyone who taught me how to deal with it."

Expelled from his first high school, Delonte re-enrolled at Luke C. Moore High School. It was there that he first encountered Critical Exposure. It was through the program that Delonte said he felt respected for the first time.

"They gave me a chance to share my pain rather than telling me what they think is right," he said. "In Critical Exposure, I felt like I would be accepted no matter what I said."

Through conversations about leadership and advocacy, Delonte learned about right and wrong, and about systems of power. He also learned about the power of a photograph.

"I didn't think about how much meaning (a photo) had until I thought about using one for change," he said. "A picture is probably worth more than a thousand words. Maybe a million."